Cherry Bombe Issue 23 Future of Food .

Dear beloved Cherry Bombe staff, I wanted to take a moment to express my excitement for the upcoming fall issue. Whether or not I get picked is trivial compared to the profound effect your question has had on me. It compelled me to engage in a deep reflection on the transformative nature of life. I found myself simmering in thoughtful contemplation and approaching life with a sense of tranquility and introspection as I was rolling brioche dough as work. I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to express these sentiments through my writing . Thank you for inspiring me and I wish you all a fantastic year ahead. With Gratitude, Lisa Bi

Lisa Bi, Yourcousinbi

5/15/20245 min read

Reviving Vietnamese Homestyle Cuisine, Buried by Assimilation

"Baann Meiii? Cool, can I have a pork banh mi?", a man asked as he read the name of my pop-up restaurant and skimmed my menu. "Sorry, no banh mi here. My pop-up is called Ba+Me, pronounced Bahh Mehh, meaning dad and mom. But I have tapioca shrimp dumplings, savory sticky rice, and crispy turmeric crepes. These are dishes that I eat at home with my family, and they're just as delicious!", I replied. He looked confused and slightly irritated, asking, "Do you have any pho?" I responded, "No, sorry, this is what we have on the menu." I was also confused because the menu was in plain English. This was a common occurrence when I started my Vietnamese comfort food pop-up in Atlanta. Although Vietnamese food has been in America since the 1970s, it has become one-dimensional for the comfort of the American people and stagnant in my eyes.

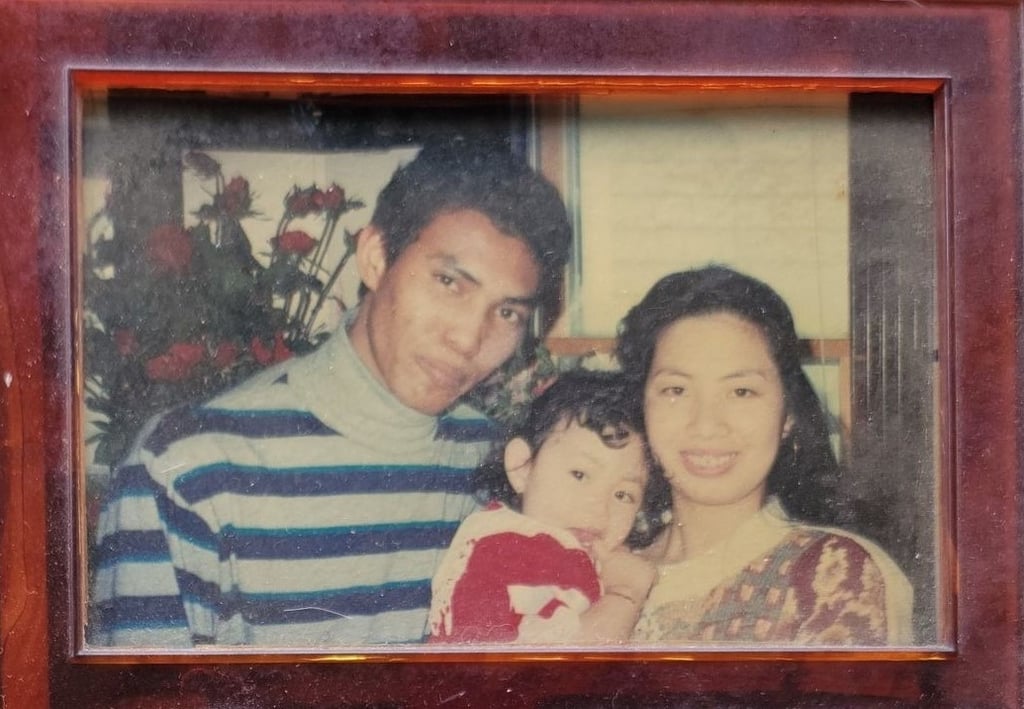

My parents arrived in Dorchester, Massachusetts as Vietnamese refugees in the 1990s. My mom was 19, carrying me in her belly, and my dad was 21, both seeking to build a better life after escaping the traumas from the aftermath of the war. They had no money and minimal English vocabulary that they learned in Singapore on their way to the U.S. They both worked multiple jobs, and their roommates helped raise me as they struggled to make a living. Both of my parents worked in a car factory assembling car pieces. My mom also cleaned houses, and my dad worked as a janitor at night and rummaged through trash in the early morning to find cans to trade in for an extra 10 to 20 cents because every cent counted. Despite their hardships, my mother still managed to prepare a home-cooked meal for our family. My parents weren't the warmest of people through affection or affirmations. The rare times I felt love or connection with them was through a cooked meal that warmed my belly. They often taught me not to stand out, not to be too loud. Their love language was feeding me and protecting me from harm by making me blend in. My parents were often conflicted about raising me as a Vietnamese or an American child. I would speak Vietnamese, but it wasn't as important to read or write in Vietnamese as it was to read or write in English.

My mother would make bun bo hue, and I would dump so much shrimp paste and Thai chilis in it, begging for all the pig blood cubes. One day, I asked my mother to pack it for lunch, and she said no without explanation but packed fried rice instead. Her fried rice wasn't typical; it was seasoned with fish sauce and so much garlic. I microwaved it at school for lunch and immediately drew negative attention. Kids said things like "Eww, disgusting, smells like farts." I was a shy kid and didn't make friends easily. I approached a well-known Vietnamese girl in school who could easily blend in with American girls in the way she spoke and the things she liked. I saw an empty seat and decided to sit next to her, hoping for a united front, for friendship, and indirect protection from all the jeers from the American kids. Instead, she told me my lunch was gross because it reeked of fish and that I should have the mac and cheese from the cafeteria or Mama Ramen instead. She gave me an extra one from her bag. I remember the silver bag, shrimp tom yum flavor. She crunched up the noodles, poured the seasoning, and shook it up. My heart sank a little when I threw my fried rice away in the trash, but it also swelled with happiness from the acceptance of integrating with the group, not realizing that it wasn't integration but rather assimilation that was happening.

Years later as an adult, I reflect on my journey. A significant moment stands out, one that truly shaped my path. It was during the pandemic when I worked as a paramedic, witnessing the unpredictable nature of death becoming more prevalent. No longer were deaths solely attributed to known causes like cancer, overdoses, or car accidents. Instead, it became a 21-year-old with no medical history succumbing, or a seemingly healthy 55-year-old woman being placed on a ventilator the day after being diagnosed with the "flu", unbeknownst to us then that it was COVID-19 causing such chaos. The uncertainty of those days brought me face to face with the fragility of life and the importance of family and connection. It reminded me of the fleeting nature of existence and the profound impact that shared moments and meaningful relationships can have. In that realization, I felt resolved to reconnect with my own family, to bridge the gaps that had formed over time, and to create memories grounded in love and heritage.

So I began searching for homestyle dishes to pick up and bring to my parents' house for dinner, but I encountered a problem. When I visited various Vietnamese restaurants, I noticed that their menus predominantly featured pho and banh mi. While these dishes have their place and are undoubtedly delicious, I couldn't help but feel that our cuisine had been simplified and limited to conform to narrow expectations. Determined to reconnect with the flavors that make me feel at home, I asked my mother for our family's recipes and scoured Vietnamese articles and recipes online to recreate them, making adjustments to suit my family's preferences. As I cooked for my family and myself, I realized that I may not be the only one yearning for these authentic dishes.

This realization led me to embark on a new venture – my pop-up restaurant, Ba+Me. Its purpose is to create an atmosphere where people feel like family, where I can ask them about their day and serve them the vibrant and deep Vietnamese homestyle cuisine that I cherished at my family's dinner table. I wanted to provide a sense of welcome and love that warms their bellies. Despite my parents' concerns and their belief that no one would be interested in the food, not because it lacked deliciousness, but because it was unfamiliar and seemingly expensive, I remained determined. They saw my menu and were bewildered by the prices, worried that I wouldn't find success. They held onto the notion that Vietnamese cuisine should be inexpensive, as if our food couldn't be equally valuable and worthy as the expensive Italian cuisine.

However, Vietnamese cuisine deserves to be celebrated and valued just as much as any other cuisine. Ba+Me, began with me reconnecting with my family . But became so much more than that, it became a testament to the resilience of not just the Vietnamese people but the immigrant life, a tribute to the sacrifices my parents made, and a way to honor the generations that came before me. The homestyle dishes I offer at Ba+Me, such as tapioca shrimp dumplings, savory sticky rice, and crispy turmeric crepes, are just a glimpse into the vast array of flavors that our heritage holds. These dishes were once hidden, confined to the walls of our homes, not because they were deemed inferior, but because our previous generations faced the challenges of assimilation, survival, and the need to please unfamiliar palates. They didn't have the luxury or the courage to serve these dishes openly, fearing financial losses and the potential to alienate customers. Navigating a complex balance between preserving their culture and assimilating into a new society, their culinary offerings often became simplified, catering to the perceived preferences of the majority. The future of food lies in being unapologetically bold and authentic, in breaking free from the constraints of limited menus and showcasing the full spectrum of our culinary treasures. The future is inspiring others to embrace their own cultural roots, to discover the richness of their heritage, and to find solace and joy in the flavors that have shaped their lives. The Future is redefining the narrative, allowing the true essence of homestyle cuisine of any kind to shine brightly, bridging cultures and creating a culinary experience that is both unforgettable and transformative.